Abstract

Depression represents the foremost global cause of disability, impacting more than 300 million individuals worldwide. Nutritional factors such as vitamin D₃, magnesium, and zinc have received increasing attention for their potential roles in mood regulation through effects on neuroinflammation, neurotransmission, and endocrine function; however, clinical findings remain inconsistent. This systematic review evaluated the effects of vitamin D₃ supplementation, alone or combined with magnesium or zinc, on depressive symptoms in adults, with emphasis on baseline deficiency status and dosing strategies. A comprehensive search of electronic databases (2000–2025) identified randomized controlled trials assessing vitamin D₃ supplementation with or without magnesium or zinc in adults with depression-related outcomes. Fifteen RCTs met the inclusion criteria and were qualitatively synthesized. Short-term, high-dose vitamin D₃ regimens (e.g., 50,000 IU weekly or biweekly for 6–12 weeks) were most consistently associated with reductions in depressive symptoms, particularly among individuals with documented vitamin D deficiency or mild to moderate depression. Low-dose daily or intermittent supplementation in generally healthy individuals who have adequate or sufficient vitamin D showed limited benefit. Magnesium co-supplementation improved vitamin D status and selected inflammatory markers, while zinc supplementation demonstrated mood benefits in specific populations; however, synergistic effects were inconsistent. Vitamin D₃ supplementation appears most beneficial for depressive symptoms when correcting a confirmed deficiency. High-dose repletion followed by maintenance dosing (600–800 IU/day) with therapeutic monitoring is reasonable. Magnesium or zinc supplementation should be reserved for documented deficiencies. Further high-quality RCTs are warranted. Keywords: vitamin D₃, magnesium, zinc, mode, depression, supplementation, randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Introduction

Depression is a globally prevalent and disabling mood disorder, characterized by persistent sadness, loss of interest, cognitive impairment, and functional decline. According to the World Health Organization, depression affects more than 332 million people worldwide and is a leading contributor to the global burden of disease.[1] In the United States, the National Institute of Mental Health reports that approximately 8.3% of adults, over 21 million people, experienced a major depressive episode in 2021 alone.[2] Depression not only impairs social and occupational functioning but also increases the risk of chronic diseases, suicide, and economic strain. The annual cost of depression in the U.S. is estimated at over $210 billion, including both direct and indirect healthcare expenditures.[3] Despite widespread access to antidepressant medications and cognitive therapies, remission rates remain suboptimal, with treatment-resistant depression affecting nearly one-third of patients.[4]

The pathophysiology of depression is multifactorial, involving both psychosocial and biological contributors. Neurobiological models point to disturbances in monoamine neurotransmitters, especially serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, as central to depressive symptoms. Inflammation has also been implicated; elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α are associated with disruptions in neurobiological processes involved with depression.[5] Dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in hypercortisolemia, is frequently observed in depressed individuals and contributes to hippocampal atrophy and cognitive decline.[6] Hormonal fluctuations such as estrogen, progesterone, thyroxine, and triiodothyronine also modulate mood and may precipitate depressive episodes. Beyond these mechanisms, growing attention has been given to nutritional deficiencies as modifiable contributors to depression risk, particularly deficiencies in vitamin D₃, magnesium, and zinc.

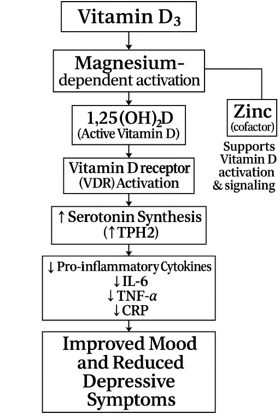

Vitamin D₃ (cholecalciferol) plays an essential role in brain development and function. Its receptors and activating enzymes are widely distributed in brain regions involved in emotion regulation, including the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Biologically, vitamin D₃ enhances serotonin synthesis by upregulating tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2).[7] Epidemiological studies have consistently linked low serum vitamin D levels with higher depressive symptom burden.[8] Risk factors for vitamin D₃ deficiency include limited sun exposure, older age, darker skin pigmentation, obesity, living in high-latitude regions, and indoor lifestyles.[9] Dietary sources of vitamin D₃ are limited, primarily found in fatty fish (e.g., salmon, sardines), egg yolks, and fortified dairy or plant-based products. According to the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements, the recommended daily allowance (RDA) for adults ranges from 600–800 IU, but many experts suggest 1000–2000 IU daily for optimal serum levels, particularly in those with baseline insufficiency.[10]

Magnesium, the second most abundant intracellular cation, is also critical to mental health. It serves as a cofactor in over 300 enzymatic reactions, including those involved in neurotransmitter production, NMDA receptor regulation, and HPA axis stabilization. Magnesium exerts antidepressant effects through several mechanisms, including modulation of glutamatergic transmission via NMDA receptor antagonism, facilitation of serotonergic neurotransmission, and attenuation of oxidative stress. It also regulates intracellular calcium homeostasis and nitric oxide signaling, thereby preserving neuronal integrity and preventing excitotoxicity associated with magnesium deficiency.[11] Dietary magnesium is found in leafy greens, nuts, legumes, whole grains, and seeds; however, modern diets high in processed foods often lack sufficient magnesium content. Subclinical magnesium deficiency is common, particularly among older adults, individuals with gastrointestinal disorders, and those with high alcohol intake. The recommended daily intake ranges from 310–420 mg for adults, depending on age and sex (NIH ODS – Magnesium).[12]

Notably, magnesium plays a synergistic role in vitamin D metabolism. It is required for the enzymatic hydroxylation of vitamin D in the liver (25-hydroxylase) and kidneys (1α-hydroxylase), as well as for its binding to vitamin D-binding protein, which is necessary for systemic transport. Without sufficient magnesium, vitamin D₃ activation and utilization are impaired, potentially rendering supplementation ineffective.[13] Despite these mechanistic links, randomized trials examining the effects of vitamin D₃ or magnesium on depression have produced mixed results, possibly due to heterogeneity in study populations, baseline deficiencies, dosage, and intervention duration.

Zinc is an essential trace mineral that supports vitamin D function by stabilizing the vitamin D receptor (VDR) and enabling proper gene activation. Without sufficient zinc, vitamin D cannot effectively fulfill its physiological roles, even with normal blood levels.[14] Zinc also plays a role in converting vitamin D to its active form, and vitamin D helps regulate immune-related zinc transporters, highlighting their synergistic relationship.[15] Clinical studies have shown that zinc supplementation can boost vitamin D levels and improve mood, especially in postmenopausal women receiving both nutrients.[16] Together, zinc and vitamin D contribute to immune balance, stress response, and emotional well-being. However, zinc deficiency remains common due to limited intake or absorption, particularly in older adults and those with restrictive diets. To address inconsistencies in existing evidence, we conducted this systematic review evaluating vitamin D₃ supplementation, alone or combined with magnesium and zinc, for reducing depressive symptoms in adults. Through a critical synthesis of RCT data, this review seeks to clarify the therapeutic potential of these widely available, safe, and low-cost nutrients for improving mental health outcomes.

Figure 1: Influence of Magnesium and Zinc on Vitamin D3 activation and their impact on mood and depression. [5, 6,13,15,16]

Methods

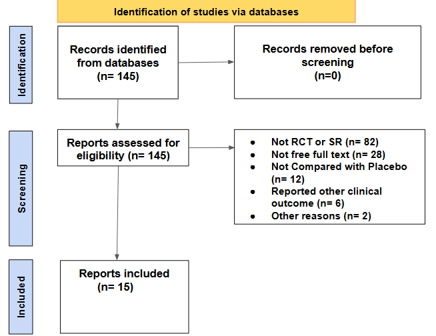

A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed, Google Scholar, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library from 2000 to 2025. Search terms included: “vitamin D”, “cholecalciferol”, “magnesium”, “zinc”, “depression”, “mood”, “randomized controlled trial”, and “RCT” using Boolean operators. Initially, 145 results were identified, and all were tested for eligibility. Of the 145 studies, 15 were selected based on their data regarding vitamin D3, zinc, and magnesium in relation to depression symptoms and mode. Participant sample sizes and outcome measures were systematically evaluated to determine the independent effects of vitamin D3 on depressive symptoms. Further analyses were conducted to assess the combined influence of vitamin D3 with zinc and magnesium on depression severity and symptom reduction.

Figure 2: Flow chart and Study showing the number of articles identified and included in the study

Results and Discussion

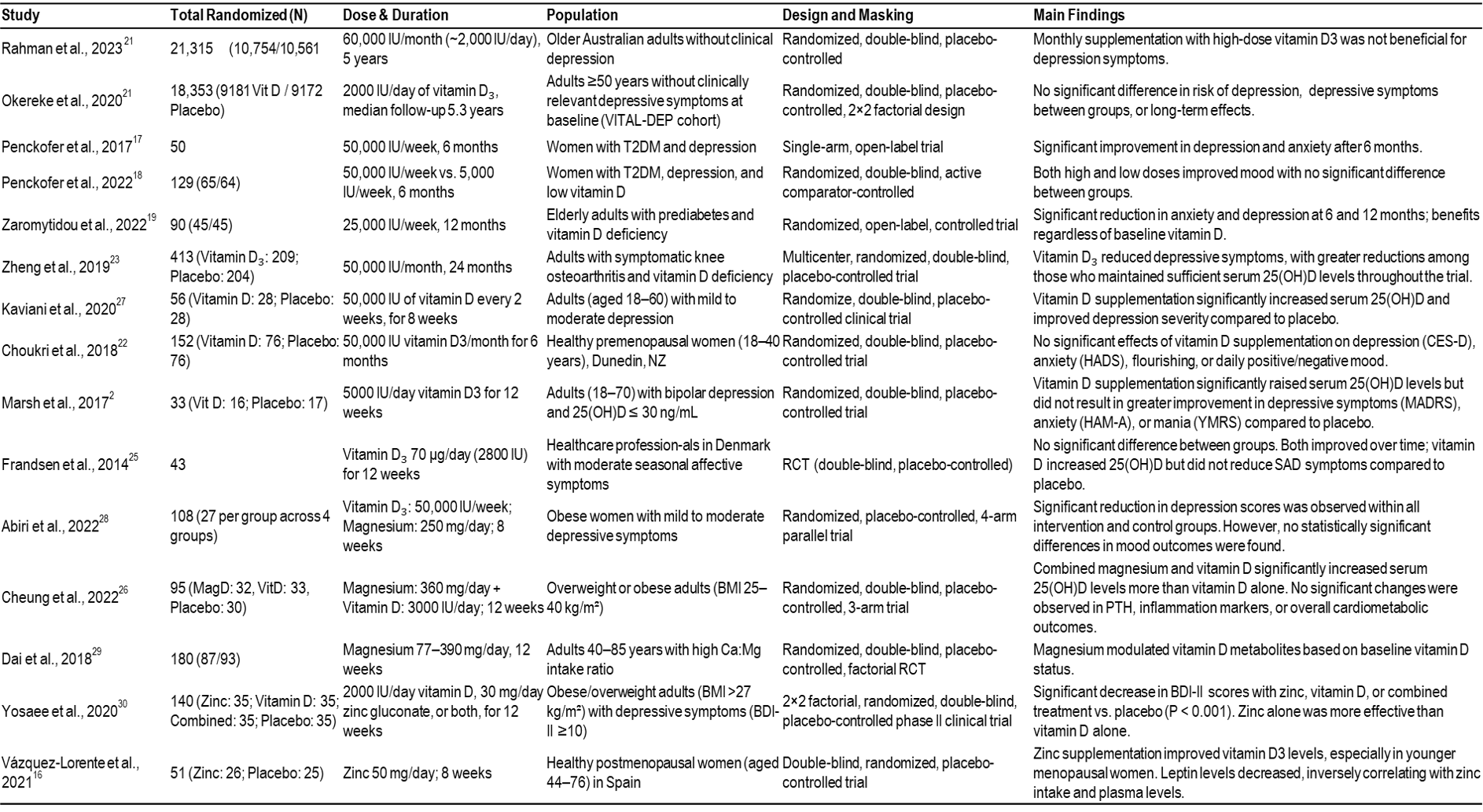

A total of fifteen RCTs met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review (see Table 1). The goal was set to collectively investigate the impact of vitamin D₃ supplementation with or without concomitant magnesium or zinc on depressive symptoms in adults. The overall evidence indicates that the efficacy of vitamin D₃ supplementation depends on several key variables: the administered dose, dosing frequency, and participant characteristics. Notably, weekly high-dose regimens (most frequently 50,000 IU for 6–12 weeks) emerged as the dosing strategy most consistently associated with improvements in depressive symptoms. Two studies by Penckofer et al. demonstrated significant reductions in depression and anxiety scores among women with type 2 diabetes receiving weekly high-dose vitamin D₃ supplementation.[17] [18] Similarly, Zaromytidou et al. reported sustained improvements in mood outcomes among elderly adults with prediabetes and vitamin D deficiency during a 12-month intervention.[19] Additionally, an RCT employing biweekly administration of 50,000 IU vitamin D₃ for eight weeks yielded clinically meaningful reductions in depressive symptoms in individuals with mild to moderate depression.[27] Collectively, these findings suggest that higher-dose, weekly vitamin D₃ supplementation may confer significant antidepressant benefits in individuals with baseline vitamin D deficiency. This effect is particularly evident in those presenting with mild to moderate depression.

Despite these positive signals, the evidence base remains inconsistent. Several well-designed RCTs have documented improvements in depressive symptoms with vitamin D₃ supplementation in vitamin D-deficient populations, particularly when higher-dose regimens were used. However, larger trials have failed to demonstrate either a preventive or therapeutic effect in unselected adult cohorts. This discrepancy underscores the importance of baseline vitamin D status, dosing strategy, and study population.[20] [21] For instance, Zheng et al. reported significant reductions in depressive symptoms with monthly administration of 50,000 IU over 24 months, whereas other studies observed no psychological benefit despite increases in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations.[21] [22] [23] In contrast, three separate trials employing daily supplementation regimens (2,000–5,000 IU/day) consistently increased serum 25(OH)D levels but failed to produce significant improvements in depression scores, potentially reflecting placebo effects, inadequate dosing intensity, or baseline vitamin D sufficiency.[24] [25] [26]

Table 1: Studies involving vitamin D3 supplementation with and without other supplementations. [21] [20] [17] [18] [19] [23] [27] [22] [24] [25] [28] [26] [29] [30] [16]

The potential role of magnesium as a modulator of vitamin D efficacy was explored in three included studies. Abiri et al. demonstrated that co-supplementation with vitamin D (50,000 IU/week) and magnesium (250 mg/day) for eight weeks favorably altered selected biomarkers related to neuroinflammation and neurotrophic signaling (including BDNF, IL-6, and TNF-α). However, there were no statistically significant differences in depression scores between intervention groups.[28] Similarly, Cheung et al. found that combined supplementation with magnesium (360 mg/day) and vitamin D (3,000 IU/day) for 12 weeks led to a greater increase in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations compared with vitamin D alone, although no significant effects on mood outcomes or inflammatory markers were detected.[26]

In contrast, Dai et al. showed that magnesium intake alone modulated circulating vitamin D metabolites, with effects varying by baseline vitamin D status.[29] Additionally, a randomized controlled trial found that magnesium oxide (500 mg/day) administered for eight weeks significantly reduced depression scores in hypomagnesemic patients relative to placebo.[31] Taken together, these findings suggest that magnesium may support vitamin D metabolism and downstream physiological activity, particularly in individuals with magnesium deficiency. Although current evidence does not consistently demonstrate that vitamin D magnesium co-supplementation confers additional clinically meaningful benefits for depressive symptoms beyond correction of underlying deficiencies.

Zinc has also been investigated as a potentially interactive nutrient within the vitamin D pathway, primarily due to its role in supporting vitamin D receptor (VDR) structure and downstream gene transcription rather than direct activation of vitamin D. Evidence for this interaction is limited but suggestive. One randomized trial demonstrated that zinc supplementation was associated with higher circulating vitamin D₃ concentrations in a majority of participants, suggesting a potential role for zinc in supporting vitamin D status.[16] In another clinical trial involving obese adults, combined supplementation with vitamin D and zinc was associated with improvements in depressive symptoms. Notably, both vitamin D and zinc administered individually were also associated with mood improvements.[30] Taken together, these findings suggest a potential interaction between zinc and vitamin D in influencing serum vitamin D levels and mood-related outcomes, although the available evidence remains limited and heterogeneous.

These observations align with conclusions from recent meta-analyses of vitamin D supplementation and depressive symptoms. One meta-analysis found significant reductions in depressive symptoms among individuals with baseline serum 25(OH)D concentrations above 50 nmol/L, but not in those with lower baseline levels.[32]. Another meta-analysis reported a modest overall effect size (Hedges’ g ≈ −0.32), with stronger effects observed in individuals with major depressive disorder or perinatal depression.[33] Subgroup analyses further indicated greater benefit in short-duration trials (<12 weeks) and with vitamin D doses of at least 2,000 IU/day, whereas minimal effects were observed in healthy populations without baseline depressive symptoms. Supporting these findings, a randomized controlled trial in pregnant women showed that daily supplementation with 2,000 IU of vitamin D₃ during late pregnancy significantly reduced perinatal depression scores, and a separate trial in postpartum women reported that biweekly administration of 50,000 IU vitamin D₃, with or without calcium, resulted in significant symptom improvements over eight weeks compared with placebo.[34] [35]

Vitamin D₃ is a fat-soluble secosteroid with a relatively long circulating half-life of approximately 15–25 days for its primary metabolite, 25(OH)D, supporting the feasibility of weekly or biweekly dosing regimens in clinical practice. Absorption occurs mainly in the small intestine and is enhanced by dietary fat, though adequate absorption is maintained under typical dietary conditions. Serum 25(OH)D concentrations above 50 nmol/L (20 ng/mL) are generally considered sufficient for most individuals, and daily intakes up to 4,000 IU are regarded as safe.[10] [36] Vitamin D toxicity is rare and typically associated with sustained intakes exceeding 10,000 IU/day.[36] Long-term administration of 50,000 IU weekly has been reported to be well tolerated in clinical settings, without evidence of hypercalcemia or renal dysfunction.[37] These pharmacokinetic and safety considerations support the targeted use of higher-dose vitamin D₃ supplementation in deficient or at-risk populations, rather than indiscriminate supplementation in the general population.

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the established daily value (DV) for vitamin D is 20 mcg (800 IU) for adults, generally sufficient for maintenance in healthy individuals.[38] However, clinical management of deficiency often requires substantially higher doses such as 6,000 IU daily or up to 50,000 IU weekly, especially when serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels fall below 12 ng/mL.[9] When in combination with magnesium or zinc, there was a greater effect towards depressive symptom alleviation due to the increased activation of vitamin D by these elements.

Conclusion

The evidence from randomized controlled trials, the impact of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms remains equivocal. Nonetheless, a discernible trend points to potential benefit for individuals with mild to moderate depression who are vitamin D deficient at baseline. The most pronounced effects were observed in studies enrolling participants with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations below roughly 25–30 nmol/L (10–12 ng/mL) and utilizing higher-dose regimens over a defined repletion period. Importantly, vitamin D is a nutritional supplement rather than a pharmacologic antidepressant, and thus should not be considered a primary treatment for depressive disorders. Instead, supplementation should be conceptualized as an adjunctive measure to correct an underlying nutritional deficit that may contribute to depressive symptomatology. In patients with confirmed deficiency, short-term repletion with high-dose vitamin D₃, such as 50,000 IU weekly for several weeks, effectively restores serum 25(OH)D concentrations to sufficiency. This strategy should be undertaken with regular biochemical monitoring to ensure safety and prevent excessive dosing. Upon achieving adequate vitamin D status, transition to a maintenance regimen, commonly 800–1,000 IU daily in accordance with U.S. guidelines, can sustain serum levels within the optimal range. Decisions regarding magnesium or zinc co-supplementation should be guided by laboratory evidence of deficiency; routine co-administration is not currently supported for individuals with normal micronutrient status, though targeted correction of deficiencies may enhance the physiological response to vitamin D. Finally, before initiating vitamin D or any nutritional supplement, patients should consult with a qualified healthcare professional to assess baseline nutritional status, evaluate potential risks, and ensure appropriate dosing and monitoring. This individualized, deficiency-guided approach aligns with both the existing clinical evidence and principles of safe supplementation.

Limitations

A small number of RCTs were available, as well as the differing populations. Differences in mental testing scales, dosing from study to study, and additional supplementation components.

Acknowledgement

The author gratefully acknowledges the valuable contributions of Dr. Randy Mullins, Associate Professor and Chair of the Department at the Appalachian College of Pharmacy, for his expert review and comprehensive editorial support, which greatly enhanced the quality and clarity of this article. The author also extends sincere thanks to Nishi Chowdhury, a Public Health student at The George Washington University, for carefully verifying all references and assisting with grammatical review during the editing process.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Depressive disorder (depression). Accessed December 03, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

- Major Depression – National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Accessed December 04, 2025.

- The Economic Burden of Adults With Major Depressive Disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). Accessed December 05, 2025.

- Acute and Longer-Term Outcomes in Depressed Outpatients Requiring One or Several Treatment Steps: A STAR*D Report | American Journal of Psychiatry. Accessed December 03, 2025.

- Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):732-741. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029

- Pariante CM, Lightman SL. The HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(9):464-468. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.006

- Patrick RP, Ames BN. Vitamin D hormone regulates serotonin synthesis. Part 1: relevance for autism. FASEB J Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol. 2014;28(6):2398-2413. doi:10.1096/fj.13-246546

- Anglin RES, Samaan Z, Walter SD, McDonald SD. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(2):100-107. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.111.106666

- Kaur J, Khare S, Sizar O, Givler A. Vitamin D Deficiency. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed December 02, 2025.

- Office of Dietary Supplements – Vitamin D. Accessed December 04, 2025.

- Eby GA, Eby KL. Rapid recovery from major depression using magnesium treatment. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67(2):362-370. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.01.047

- Barbagallo M, Veronese N, Dominguez LJ. Magnesium in Aging, Health and Diseases. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):463. doi:10.3390/nu13020463

- Uwitonze AM, Razzaque MS. Role of Magnesium in Vitamin D Activation and Function. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2018;118(3):181-189. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2018.037

- Amos A, Razzaque MS. Zinc and its role in vitamin D function. Curr Res Physiol. 2022;5:203-207. doi:10.1016/j.crphys.2022.04.001

- Zinc and Vitamin D Together: Science-Backed Benefits. Supplements Studio. October 7, 2025. Accessed December 06, 2025.

- Vázquez-Lorente H, Molina-López J, Herrera-Quintana L, Gamarra-Morales Y, López-González B, Planells E. Effectiveness of eight-week zinc supplementation on vitamin D3 status and leptin levels in a population of postmenopausal women: a double-blind randomized trial. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2021;65:126730. doi:10.1016/j.jtemb.2021.126730

- Penckofer S, Byrn M, Adams W, et al. Vitamin D Supplementation Improves Mood in Women with Type 2 Diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:8232863. doi:10.1155/2017/8232863

- Penckofer S, Ridosh M, Adams W, et al. Vitamin D Supplementation for the Treatment of Depressive Symptoms in Women with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Diabetes Res. 2022;2022:4090807. doi:10.1155/2022/4090807

- Zaromytidou E, Koufakis T, Dimakopoulos G, et al. Vitamin D Alleviates Anxiety and Depression in Elderly People with Prediabetes: A Randomized Controlled Study. Metabolites. 2022;12(10):884. doi:10.3390/metabo12100884

- Okereke OI, Reynolds CF, Mischoulon D, et al. Effect of Long-term Vitamin D3 Supplementation vs Placebo on Risk of Depression or Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptoms and on Change in Mood Scores: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;324(5):471-480. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.10224

- Rahman ST, Waterhouse M, Romero BD, et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on depression in older Australian adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2023;38(1):e5847. doi:10.1002/gps.5847

- Choukri MA, Conner TS, Haszard JJ, Harper MJ, Houghton LA. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms and psychological wellbeing in healthy adult women: a double-blind randomised controlled clinical trial. J Nutr Sci. 2018;7:e23. doi:10.1017/jns.2018.14

- Zheng S, Jin X, Cicuttini F, et al. Maintaining Vitamin D Sufficiency Is Associated with Improved Structural and Symptomatic Outcomes in Knee Osteoarthritis. Am J Med. 2017;130(10):1211-1218. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.038

- Marsh WK, Penny JL, Rothschild AJ. Vitamin D supplementation in bipolar depression: A double blind placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;95:48-53. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.07.021

- Frandsen TB, Pareek M, Hansen JP, Nielsen CT. Vitamin D supplementation for treatment of seasonal affective symptoms in healthcare professionals: a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):528. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-528

- Cheung MM, Dall RD, Shewokis PA, et al. The effect of combined magnesium and vitamin D supplementation on vitamin D status, systemic inflammation, and blood pressure: A randomized double-blinded controlled trial. Nutrition. 2022;99-100:111674. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2022.111674

- Kaviani M, Nikooyeh B, Zand H, Yaghmaei P, Neyestani TR. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on depression and some involved neurotransmitters. J Affect Disord. 2020;269:28-35. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.029

- Abiri B, Sarbakhsh P, Vafa M. Randomized study of the effects of vitamin D and/or magnesium supplementation on mood, serum levels of BDNF, inflammation, and SIRT1 in obese women with mild to moderate depressive symptoms. Nutr Neurosci. 2022;25(10):2123-2135. doi:10.1080/1028415X.2021.1945859

- Dai Q, Zhu X, Manson JE, et al. Magnesium status and supplementation influence vitamin D status and metabolism: results from a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(6):1249-1258. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqy274

- Yosaee S, Soltani S, Esteghamati A, et al. Effects of zinc, vitamin D, and their co-supplementation on mood, serum cortisol, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in patients with obesity and mild to moderate depressive symptoms: A phase II, 12-wk, 2 × 2 factorial design, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition. 2020;71:110601. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2019.110601

- Rajizadeh A, Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Yassini-Ardakani M, Dehghani A. Effect of magnesium supplementation on depression status in depressed patients with magnesium deficiency: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition. 2017;35:56-60. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2016.10.014

- Wang R, Xu F, Xia X, et al. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on primary depression: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2024;344:653-661. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.10.021

- Mikola T, Marx W, Lane MM, et al. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023;63(33):11784-11801. doi:10.1080/10408398.2022.2096560

- Vaziri F, Nasiri S, Tavana Z, Dabbaghmanesh MH, Sharif F, Jafari P. A randomized controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation on perinatal depression: in Iranian pregnant mothers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:239. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-1024-7

- Amini S, Amani R, Jafarirad S, Cheraghian B, Sayyah M, Hemmati AA. The effect of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on inflammatory biomarkers, estradiol levels and severity of symptoms in women with postpartum depression: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Nutr Neurosci. 2022;25(1):22-32. doi:10.1080/1028415X.2019.1707396

- Vitamin D – Mayo Clinic. Accessed December 05, 2025.

- Jetty V, Glueck CJ, Wang P, et al. Safety of 50,000-100,000 Units of Vitamin D3/Week in Vitamin D-Deficient, Hypercholesterolemic Patients with Reversible Statin Intolerance. North Am J Med Sci. 2016;8(3):156-162. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.179133

- Program HF. Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels. FDA. Published online September 9, 2024. Accessed December 06, 2025.

The Effects of Vitamin D₃ Supplementation With or Without Magnesium and Zinc on Depression in Adults: A Systematic Review © 2026 by Bhuiyan et al is licensed under Attribution 4.0 International

Note

Place of Publication: PSciP Publishing LLC, Oakwood, VA, USA.